Ancestral Access – Highlighting the Native Lands We Play On in Washington State

Washington offers an incredible playground for outdoor recreation, from skiing high altitude volcanoes in the spring to extensive networks of mountain biking and running trails. However, it’s essential to acknowledge that these lands have been inhabited for centuries by numerous indigenous nations, including the Snoqualmie tribe around North Bend (where I reside) and the Muckleshoot, Nisqually, and Puyallup tribes near Mount Rainier.

I want to briefly cover how some of these lands have been transferred from indigenous owners to recreational management agencies, highlight some of the native tribes that have lived on these lands for centuries, and share some resources for information on native areas.

How’d We Get Here?

Three primary classifications help define the relationship of previously indigenous lands:

- Ancestral Lands,

- Reservations,

- And Ceded Lands.

Ancestral lands refer to the territories a Tribe occupied and utilized traditionally. Reservations are parcels of land held in trust by the federal government for the exclusive use of a federally recognized Tribe.

However, the majority of high-impact recreation, such as skiing and mountain biking in the Cascade and Olympic National Forests, occurs on what is legally defined as “Ceded Land.”

These were vast territories sold or relinquished by Tribes to the United States government via treaties, but where the Tribes explicitly reserved specific rights.

Many recreation areas that we commonly refer to as “public land,” particularly National Forests, are more accurately labeled as “Treaty Ceded Land.” Within these areas, the Tribes retain the right to fish in their “usual and accustomed” areas and the privilege of hunting on “open and unclaimed lands”. This reservation of rights means the land is a legally shared space where Tribal rights are constitutionally protected.

Washington State currently maintains formal government-to-government relationships with 29 federally recognized Tribes, including:

- The Confederated Tribes of the Chehalis Reservation,

- Colville Confederated Tribes,

- Cowlitz Tribe,

- Hoh Tribe,

- Jamestown S’Klallam Tribe,

- Kalispel Tribe,

- Lower Elwha Klallam Tribe,

- Lummi Nation,

- Makah Tribe,

- Muckleshoot Indian Tribe,

- Nisqually Indian Tribe,

- Nooksack Indian Tribe,

- Port Gamble S’Klallam Tribe,

- Puyallup Tribe of Indians,

- Quileute Nation,

- Quinault Indian Nation,

- Samish Indian Nation,

- Sauk-Suiattle Indian Tribe,

- Shoalwater Bay Tribe,

- Skokomish Indian Tribe,

- Snoqualmie Tribe,

- Spokane Tribe,

- Squaxin Island Tribe,

- Stillaguamish Tribe,

- Suquamish Tribe,

- Swinomish Tribe,

- Tulalip Tribes,

- Upper Skagit Tribe,

- And the Confederated Tribes and Bands of the Yakama Nation.

While I won’t delve fully into the complete history of treaties between the US Government and all of these Indigenous Nations, I will highlight a few that are particularly noteworthy:

| Treaty Name | Date | Relevant Tribes (Examples) | Geographic Area Impacted | Key Implications for Recreation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treaty of Medicine Creek | 1854 | Nisqually, Puyallup, Muckleshoot | Southern Puget Sound and surrounding uplands (includes areas near I-5) | Reserved hunting and fishing rights in vast areas south of Seattle, impacting popular running/biking areas. |

| Treaty of Point Elliott | 1855 | Snoqualmoo, Suquamish, Lummi, Swinomish | Central and Northern Puget Sound regions, extending to Cascade summit (includes I-90 corridor and Mount Baker) | Covers major ski, bike, and run corridors including Snoqualmie Pass and the Mount Baker region. |

| Treaty with the Yakama | 1855 | Confederated Tribes and Bands of the Yakama Nation | Central Washington, extending from the Columbia River to the Cascade crest (includes Mount Adams and White Pass context) | Created the Yakama reservation, but reserved hunting and gathering rights throughout the vast ceded territory. |

How Do We Operate Now?

Since the execution of these land agreements, there has been major population growth and recreational development in Washington State. It doesn’t take a local to notice that mountain biking, trail running, and backcountry skiing have become much more popular in the last 15-20 years.

I want to delve into more detail on a couple of popular recreation areas around the state and how land management agencies and Indigenous nations have come together to foster outdoor recreation partnerships.

Snoqualmie Tribe & I-90 Corridor (Snoqualmie Pass)

The Snoqualmie Tribe has historically inhabited land areas covering the Raging River State Forest and Tiger Mountain State Forest, which feature extensive biking and running trails. These areas have seen exponential increases in visitation over the last few years, as mountain biking and trail running rise in popularity.

In response to this growth, the Snoqualmie Tribe has launched the Snoqualmie Tribe Ancestral Lands Movement (STALM), which seeks to educate the public on the significance of these lands and deepen respect for the landscape. The Tribe explicitly asks people to commit to experiencing the lands with mindfulness, rather than conquest. Specific, actionable ethical guidelines from STALM include staying on designated trails, picking up both personal trash and trash left by others, and properly disposing of pet waste.

You can learn more about the STALM on their site.

Crystal Mountain and the Muckleshoot Partnership

Crystal Mountain Resort, Washington’s largest ski area, operates on land historically recognized as Muckleshoot territory. The Muckleshoot Tribe and Crystal Mountain Resort partnered to create the Mountain to Sound: The Crystal Mountain Project. This program is a fully grant-funded, land-based outdoor classroom that provides culturally-centered programming for Muckleshoot youth. Students learn traditional languages, engage in meditation, and receive traditional instruction on native habitats.

Learn more about the Mountain to Sound Program.

Summary of Popular Areas and Their Indigenous Nations

For those who like tables, I’ve made a summary table below of a few popular recreation areas around Washington State.

| Recreation Area/Landmark | Activity Type | Associated Indigenous Tribe(s) | Traditional Name |

|---|---|---|---|

| Crystal Mountain Resort | Skiing/Snowboarding | Muckleshoot Indian Tribe | N/A (Near Tahoma) |

| Snoqualmie Corridor (e.g., Tiger Mt., Raging River) | Biking/Running | Snoqualmie Tribe | N/A (Part of Salish Sea) |

| Mount Rainier National Park | Running/Hiking/Climbing | Muckleshoot, Nisqually, Puyallup Tribes | Tahoma (Mother of Waters) |

| Mount Baker Ski Area / | Skiing | Lummi Nation, Nooksack Tribe | Kulshan (White Sentinel/Shooting Place) |

| Mount Adams | Hiking/Climbing | Confederated Tribes and Bands of the Yakama Nation | Pahto / Pátu |

| Deception Pass State Park | Running/Hiking | Swinomish Indian Tribal Community | N/A |

What Can You Do?

To be clear, I am not of indigenous descent and recreate regularly on indigenous lands. I am not an expert in this subject and want to respectfully acknowledge that I do not know all of the history, nor context, of many of these land agreements.

That said, I think all of us can take a moment when we head out for a backcountry ski tour, trail run, or mountain bike ride to remember a few key topics:

1. Leave No Trace

Pick up your trash, don’t disturb native wildlife, and respect the nature around you. ‘Take nothing but memories, leave nothing but footprints’ as the saying goes.

2. Land Acknowledgement

Try and learn native names for areas, like Tahoma (for Mount Rainier) and Kulshan (for Mount Baker).

3. Honor Reserved Rights

Many of these indigenous nations have worked hard to protect hunting, fishing, and land-use rights. Observe all posted rules on game, land, and water use.

Washington’s trails, rivers, and peaks are more than recreation spots; they’re ancestral homelands. By learning their histories, honoring treaty rights, and practicing respect, we can build a more mindful connection with the landscapes we love.

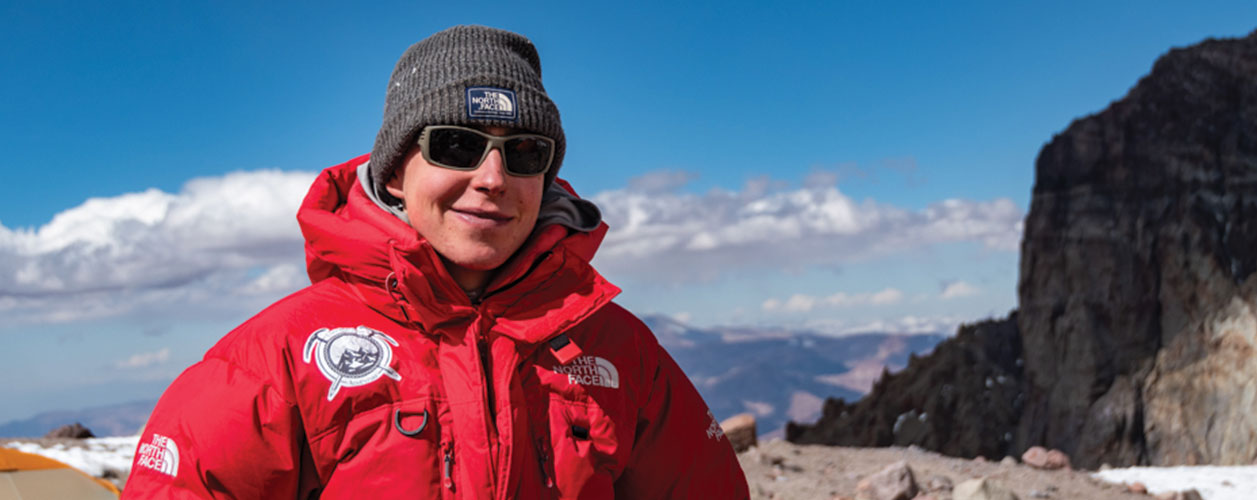

About the Gear Tester

Sam Chaneles

Sam Chaneles is an avid mountaineer and backpacker, climbing peaks in the Cascades, Mexico, Ecuador, and Africa, as well as hiking the John Muir Trail and off-trail routes in Colorado. He has climbed peaks such as Aconcagua, Mt. Rainier, Cotopaxi, Chimborazo, Kilimanjaro, and many more. Sam graduated with a B.S. in Mechanical Engineering from Georgia Tech. During his time there he was a Trip and Expedition Leader for the school’s Outdoor Recreation program (ORGT). He has led expeditions to New Zealand, Alaska, Corsica, France, and throughout the United States. Sam is based in Issaquah, WA just outside of the Cascade Mountains. You can follow Sam and his adventures on Instagram at @samchaneles, or on his website at www.engineeredforadventure.com.