How Dirtbags Make Money

Somewhere there’s an unofficial spectrum of what a dirtbag can or should be in the outdoor industry, existing solely in the minds of our own individual communities and ethos, and it ranges from the old-school cat-food-eating Stonemasters, modern van-dwellers with solar panels and twinkle lights, to the ultra-minimalist weekend warrior. What nonetheless remains a shared characteristic among the fringe-divers and relative atypicals, is the personal practice of frugality and dream-cashing—all made possible through lots of hard work or the exercising of privilege to go wherever and whenever they please. Freelance artists, writers, photographers; dedicated climbers, surfers, snowboarders, skiers; yo-yoing thru-hikers; and even the nature-loving vagabond with a rucksack: they all largely make up this “transient” population in the outdoor industry. With living on the road, on the trails, or hopping from hostel to hostel with a hitchhiker’s guide to the galaxy, how exactly do they all make their money?

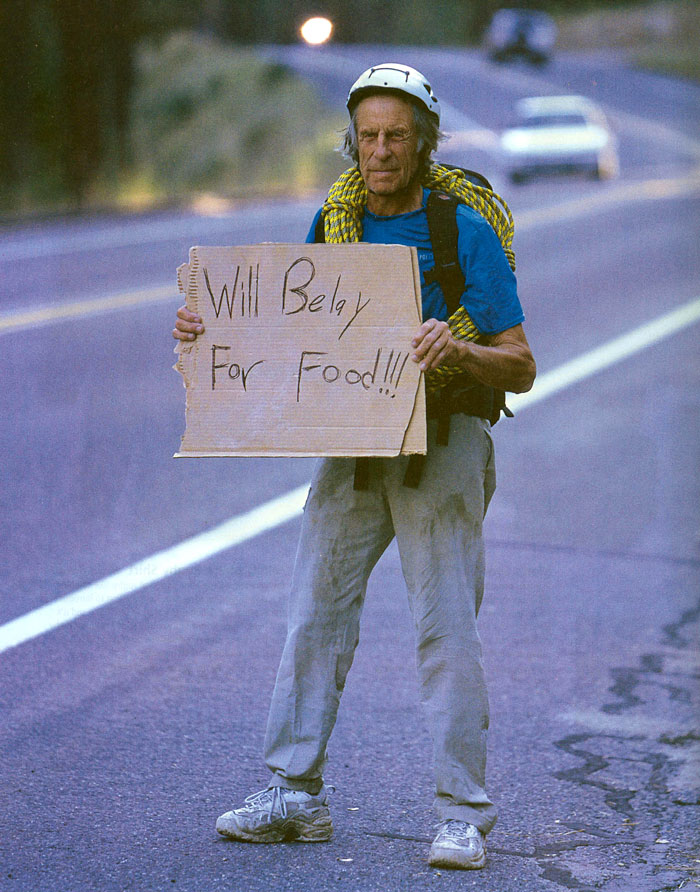

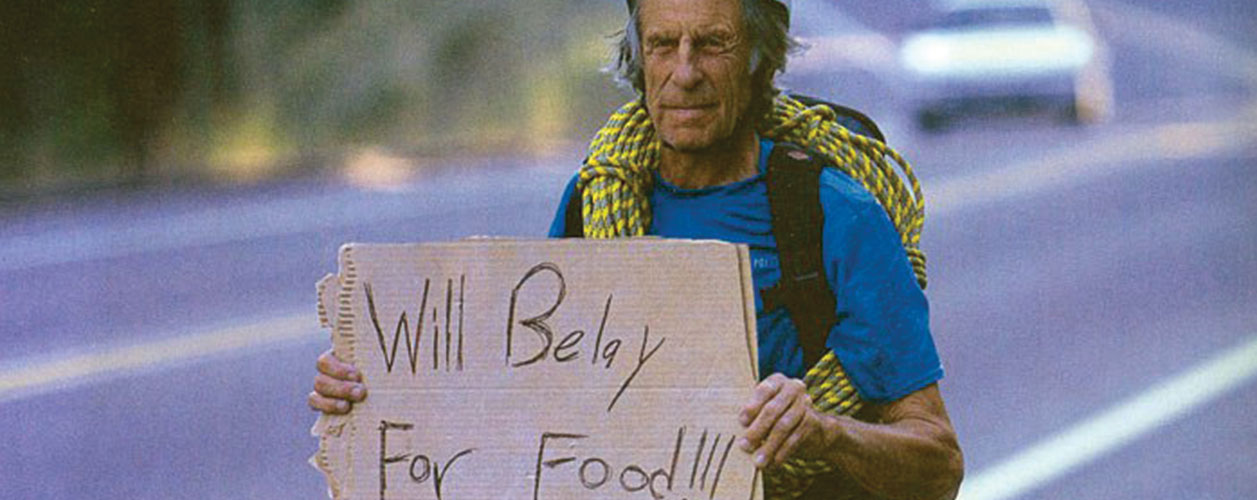

Photo by Peter Stevens, Fred Beckey in Patagonia’s Fall 2004 Catalog.

As with any lifestyle choice, there is an endless list of how people work to sustain what they need and/or want. For dirtbags, it’s not necessarily any more creative than the stereotypical freelancer, but it may seem much more desperate at times due to the fact that money isn’t likely at the forefront of their long-term efforts. A common thing to do is to sell handmade, crafty things like chalk bags, stickers, hiking gaiters; charging for personal services such as giving people rides, guiding, or laboring (like hanging Christmas lights); collecting recyclables, selling cherries on the side of the road, painting towers, or, believe it or not, shamelessly charging tourists for wanting pictures of them and their climbing gear.

Just as common is the romanticized restaurant labor from waiting tables, bussing, bartending, to dishwashing. The lure of dishwashing for Luke Mehall, author of “American Climber” for example, was that of the portability of the job. Every diner near a choice crag or surf break will likely be hiring a dishwasher. In such cases, a destination often comes first, then the tedious job search. Yet, as James Lucas wrote for Climbing Magazine, “after long bouts of low or non-employment, most people reentering the workforce tend to accept lower-paying jobs because that’s what they’re able to get.”

Photo by James Lucas, On Becoming a Modern Dirtbag

Thru-hikers with six-month ordeals along the Pacific Crest Trail often do find it difficult to readjust back into mainstream society, unless they did their homework beforehand and already have a choice job waiting (rare and idealistic). Nonetheless, those of dirtbag culture traditionally seek out the jobs that won’t care if they only stay a month or a season. Money is only there to fuel their passions and careers are not necessarily a priority.

Seasonal work is an attractive means because it provides free time for large portions of the year, so people often work non-stop at their summer camps or winter resorts to save up. I met many climbers in Yosemite National Park who would guide or bartend during the summer. Save every penny. Then hop over to Central and South America for the winter to surf their brains out or pursue climbing objectives in places like Patagonia. The work season returns and they repeat; some have been doing this for over a decade. Thus, the other attractive aspect to seasonal work is that the job is waiting for you when the season returns. I’ve heard of people collecting unemployment in-between, which raises many ethical questions, but that is a topic we won’t get into.

Overall, money-making could be a combination of everything mentioned thus far, which truly characterizes these passion lifestyles as being surprisingly flexible, but nonetheless very short-term oriented by way of constantly shifting intentions for the present ambition. Some people do hold year-round jobs in an office or classroom and still find the time to play and live with the dirtbag ethos, as Cedar Wright puts it, of “collecting experiences,” which are undeniably “more important than amassing wealth and material objects.”

Dirtbag “Psych Mike” fills his pockets by working stints for a tower-painting company, utilizing his knowledge and expertise gained from climbing. Photo courtesy of Michael Rael Armas.

In a brief interview I did with Courtney Blake, an outdoor enthusiast, she stated, “Dirtbags don’t have to be permanently dirtbagging in my opinion.” She traveled for three months after graduating college, living out of a car to climb around the U.S. and Mexico. She is now a teacher for adults with disabilities, “focusing on teaching them important life skills” to help them gain independence, achieve personal goals, and to become active members in their communities. She also works at an outdoor retail store, “giving those extra hours to save as much as possible.” Her work is rewarding to her and is an example of someone whose job isn’t just a means for travel and passion. With summers off, she still has all the time she needs to play and “sacrifice luxuries” in the tradition of the dirtbag way.

Photo courtesy of Courtney Blake.

Thus, the matter of dirtbags and money is more so about how they manage to make what they do have last as long as possible. Scraping the barrel, the grunge habits of the more old-school, “pure” dirtbag is that of dumpster diving, loop-hole thriving, or the occasional mooching off friends and kind strangers. In a Mountain Project thread about “How to Dirtbag,” there’s a great array of viewpoints regarding what’s acceptable and what’s not. Some people express thriftiness and drinking “everyone’s beer and [eating] all their food while at camp”; or pretending to be a hotel guest to “go swimming and shower in the pool bathroom.” One surfer/snowboarder suggested going Vegan to cut the costs of meat and dairy. Someone else expressed that it is best to “Understand that we don’t need most of the stuff we buy, and that we can buy most of the stuff we need at less than the suggested retail price.” Bottom line, the dirtbag mantra (no matter how you define what a dirtbag is) can be seen as thus: make enough money to sustain and only buy what you need.

Photo by Jared Akerstrom, Snowbrains

“At either end of the social spectrum there lies a leisure class.” – Eric Beck

An interesting divide in the dirtbag scene of course comes into play when social media paints the lives of dirtbags as something heroic and romantic. It’s important to keep in mind that sometimes people suffer more than they signed up for. Maybe they realized that dirtbagging is too lonely or volatile. Furthermore, for many, dirtbagging is a privilege not easily engaged with because of social and financial barriers. Maybe they have too much debt or kids they don’t feel comfortable traveling with. Maybe they have to care for a sick family member. Often the “professionals” you see in the media make most of their money by way of sponsorship or through the aid of wealthy parents. But sponsorship doesn’t always pay the bills, so it’s a misguided desire for fans and dreamers alike to seek such. Plus, it’s not a virtue to seek fame, right?

James Lucas states, “To be able to devote time to climbing, you need to be either really rich or very poor … Perhaps the only way to really get ahead in climbing is to balance a job, a climbing obsession, and a bit of a dirtbag lifestyle—to take a long-term approach to the sport. Having a little more financial support now will help your climbing more later.” Of course you can replace the term “climbing” with whatever lifestyle passion term, and it really does come down to a balance if your priorities are of maintaining mental and physical health in tandem to your art or sport. Certain sacrifices don’t always have to be made. In Lucas’s article, he writes about losing a tooth because of his dirtbag habits.

Beneath it all, minimalism and conservation still play a major role in the pursuit, but are frankly subjective to the individual. Not everyone wants to eat mayonnaise sandwiches “for a solid week in order to insure maximal caloric intake for minimal cost,” as Lynn Hill described of John “Yabo” Yablonski. But people obviously still want to experience some of the most beautiful places without having to work. What I find neat about the dirtbag lifestyle is that, once attainable, it’s truly adaptable and personal.

Camp 4 in 1968; Photography by Glen Denny, Adventure Blog.

Money will always mean something different to someone else, and even among dirtbag culture the variety of modes is often fascinating (or terrifying depending on how you look at it). As a freelancer, I have no idea how much money I will make this year and being self-employed blends easily with a reality of being unemployed. Graced with low overhead, I plan my travels as if I will have the money and somehow it all works out. For now, I’m content with this style of living. But I still have student loans and need health insurance in order to stay on top of my annual breast MRI’s and ultrasounds (thanks to genetics, I have an 80% chance of developing breast cancer during my lifetime). Balance is necessary, but money remains a means to an end. I quite enjoy the experience of shopping at the discount marts. You never know what they’re going to have on any given day. So it becomes something spontaneous. Just never buy expired beef jerky.

“He often slept in the dirt,” Hill wrote, “hitchhiked or bummed rides to get around (he worked only enough to keep clothes on his back and food in his belly)…” Yet being as “free” as the Stonemasters is impossible today, as Cedar Wright describes in his “Dirtbagging is Dead” article. So as the times change, so do the participants. While many agree with Wright, these stories of our past have undoubtedly inspired today’s version of “fringe existence” and the creative means by which people choose to experience their lives.

Alain De La Tejera works as a substitute teacher during the school year, then runs off to the mountains every summer.

Sara Aranda has a B.A. in Creative Writing and is a freelance writer and gear tester currently based on the Front Range of Colorado. Trail running, climbing, and accumulating too many notes all dominate her life. Her work has appeared in The Climbing Zine, the Boulder Weekly, The American Poetry Review, and online with Alpinist Magazine, Misadventures Magazine, and Dirtbagdreams.com. Visit her site BivyTales.com or follow along on Instagram, @HeySarawrr.

The author, Sara Aranda worked 5 different seasons in Yosemite National Park. Here, she is behind the counter of the Badger Pass alpine rental shop. Photo by Dakota Snider.

About the Gear Tester

Jess Villaire is the Marketing Manager at Outdoor Prolink. You’ll typically find her out with her doggos skiing, mountain biking, hiking, SUPing, drinking beer, or rearranging furniture. Follow her on Instagram @jessisupsidedown.

Great writing, thanks Sara.

Love the article! Here is to future Dirtbag adventures….. and to giving my one year old the privilege of being one.

Glad to hear! Cheers to dirtbag adventures!