What is ‘Corn’ Snow?

And Why are Skiers So Obsessed With It?

There is a cult-like following of skiers in the Pacific Northwest that are devoted to skiing ‘corn’ snow in the spring and summertime, long after many others have put their skis away for the year. What’s the deal? What is ‘corn snow’? And why do people love it so much??

This article will get a bit scientific at times, but I’ll try to keep it digestible and go through the basics of how corn snow forms and what it feels like to ski.

Springtime Snowpack

In many places within the United States, April 1st represents a major milestone for snowpack measurement. It’s typically the time of the year when the snowpack is the deepest or ‘fattest’. Many water management agencies track this date in particular for snowpack measurements, historically from year-to-year.

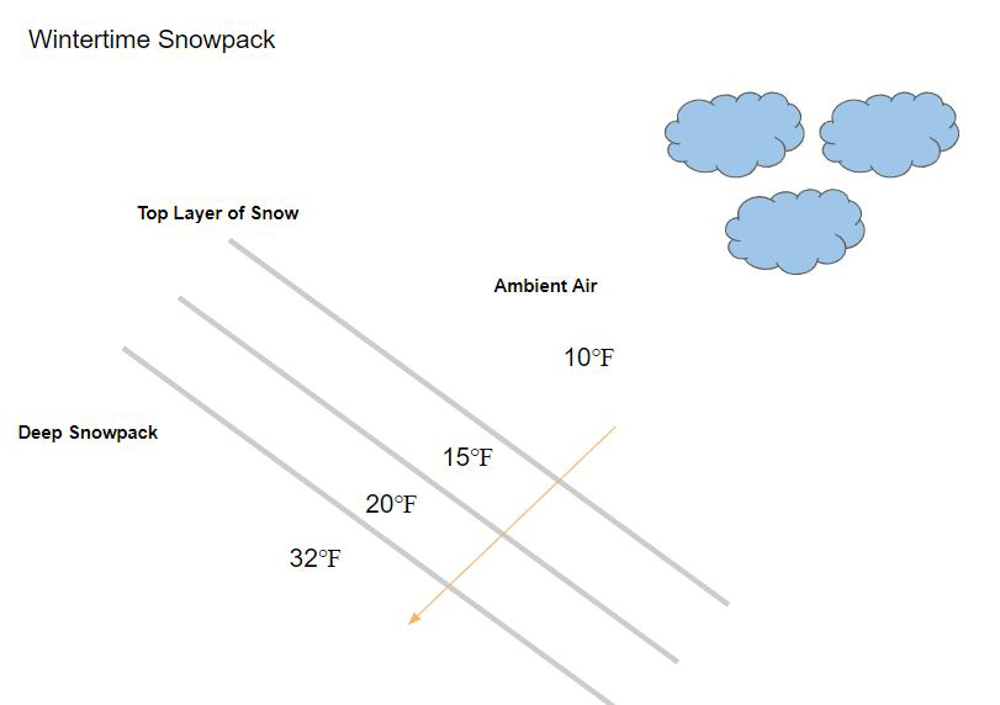

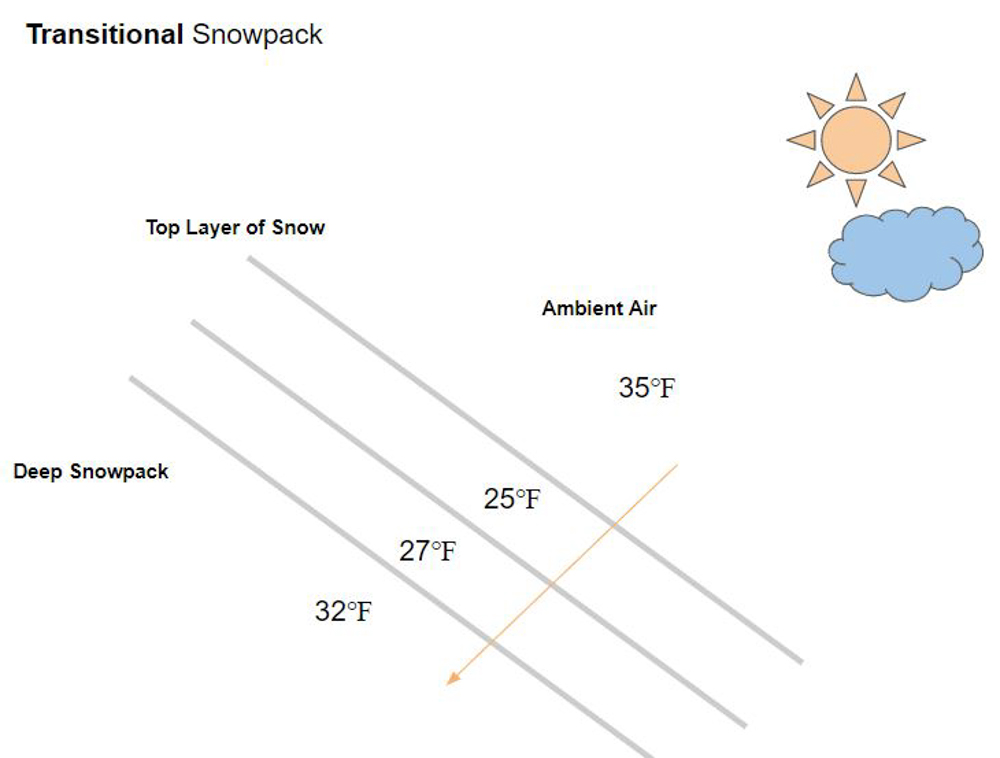

April and May are often months of ‘transition’ in the snowpack. In the wintertime there is often a temperature gradient between the top layer of snow and the layers below. This is due to the colder air temperatures during the wintertime. The top few inches of snow will be influenced by the air temperature, and often are much colder than the deeper snowpack beneath, which will be near freezing (32℉ or 0℃).

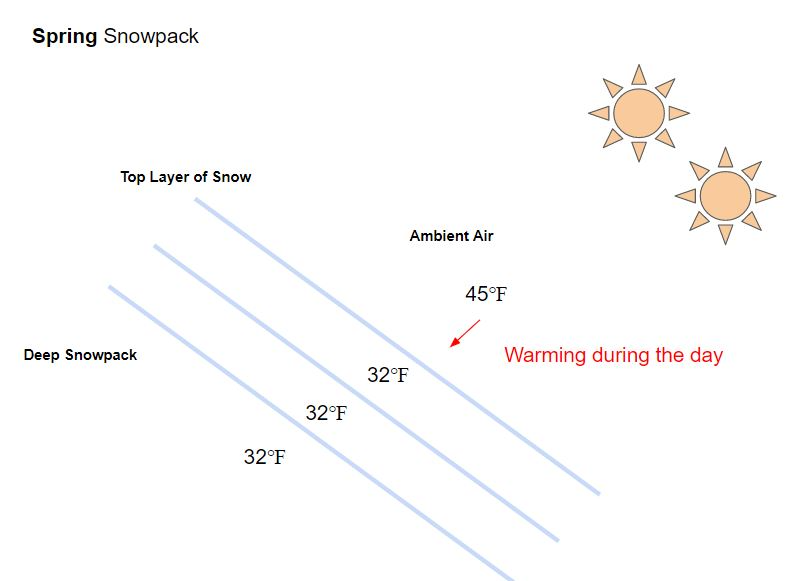

In the spring and summertime, the air temperatures warm and the snowpack begins to transition to an ‘isothermal’ state, meaning the top layer of snow warms to be closer to the 32℉ or 0℃ temperature of the deeper snowpack. During this transition period, there can often be large avalanche cycles that result from water percolating down into the deeper layers of the snowpack. This is called the ‘spring shed’. Usually this is not a good time to ski, for obvious reasons. Avalanche = BAD.

After this transition has happened, however, the snowpack is ‘isothermal’ and undergoes a daily melt-freeze cycle (assuming no new snow or precipitation). During the day, the top few inches of frozen snow will soften into what skiers call ‘corn’. It’s a slushy, consistent, and very easily skiable snow.

Imagine the snow at the base of the ski resort in the early afternoon. Kind of mushy but not total mush. As the day goes on, more and more of this snow will soften and melt due to solar input of heat. Typically by the end of the day the ‘corn’ will turn to ‘potatoes’, as skiers call it. Think of ‘potatoes’ as deep, slushy snow that is much harder to ski. Not so fun.

Then, as the sun is going down but still before the sun has totally set, the snow will begin to refreeze. There may be a brief period of ‘reverse corn’ as the ‘potatoes’ are firming back up to ‘corn’ before they completely freeze for the night. This is a VERY brief time window and some skiers try to ski ‘reverse corn’ at sunset before the day is done.

What Does ‘Corn Snow’ FEEL Like?

The best corn snow has a supportive base underneath the top layer of snow. The snow underfoot will feel consistent, supportive, and very smooth. You’ll be able to make turns without effort, pivoting from one ski edge to the other. It’s effortless.

How To Time ‘Corn-O-Clock’

Timing of corn snow is an inexact science … but is influenced by three main factors:

- Cloud Cover

- Wind

- Temperature

Ultimately, formation of corn snow is just a balance of the 3 different types of heat transfer: conduction (temperature), convection (wind), and radiation (cloud cover). The secret ‘ingredient’ to corn snow is overnight freezing of the snowpack. It’s what keeps the ‘supportable base’ underneath the surface snow.

The key to a good overnight refreeze is a clear night sky by radiative heat loss. When the sky is clear, there is radiant heat loss to outer space which makes the snowpack rock solid. It’s part of why mountaineers try to climb early in the morning hours … the snow is hard and re-frozen. If there are clouds overnight, typically the snow will poorly re-freeze. This is because of the ‘greenhouse effect’; yes, think global warming and greenhouse gasses. The clouds form a vapor barrier between the outer atmosphere and the inner atmosphere and prevent significant radiant heat loss to the colder outer space. Thus, the snow doesn’t lose as much heat overnight and doesn’t freeze as ‘deeply’.

In short, little cloud cover overnight = good refreeze.

The second ingredient to corn formation is wind, which is a form of conductive heat loss. Wind can influence how corn forms by lengthening or shortening the amount of time required to soften the surface snow. If there is wind present, corn will form later in the day as the snowpack is being convectively cooled by the surface wind. If there’s a lack of wind present, ‘corn-o-clock’ will be earlier.

In short, winds = later in the day for corn.

The third ingredient to corn formation is temperature, which is a form of conductive heat loss. The surface snow is directly in “contact” with the surface air, which has an average ‘temperature’. Typically, ski mountaineers read temperatures in terms of ‘freezing levels’, i.e. what elevation band freezing lies at. Freezing levels aren’t the ‘cheat code’ to predicting corn, though. It’s possible for the snow to stay frozen well above where the ‘freezing level’ is if there is wind or a cool and clear night sky. All that to say, it’s valuable to note where freezing levels are and use them on a ‘relative’ scale:

The higher the freezing level, the earlier the surface snow will ‘corn up’. The lower the freezing level, the later.

But wait, I never mentioned when ‘corn-o-clock’ is??? Well, if you look at your clock you’ll notice there isn’t a corn husk on it (even though I wish there was). That’s because it depends… Timing corn is all about experience and luck. Your best bet is to be on the early side, bring an extra puffy jacket, and wait at the top of your line for it to soften. There’s little harm in waiting at the top of your line by being early, as long as you are prepared to wait out the cold. There is harm in dropping your line too late and dealing with wet slides. Be early and wait for the corn!

Go Harvest!

Once you realize how delicious corn skiing can be, the length of your ski season will significantly lengthen into the spring months. It opens up so many interesting possibilities of spring ski traverses, volcanoes (check out this article I wrote on skiing volcanoes), and other big missions. You may just have to make a pilgrimage to the corn-capital of the US: the Pacific Northwest.

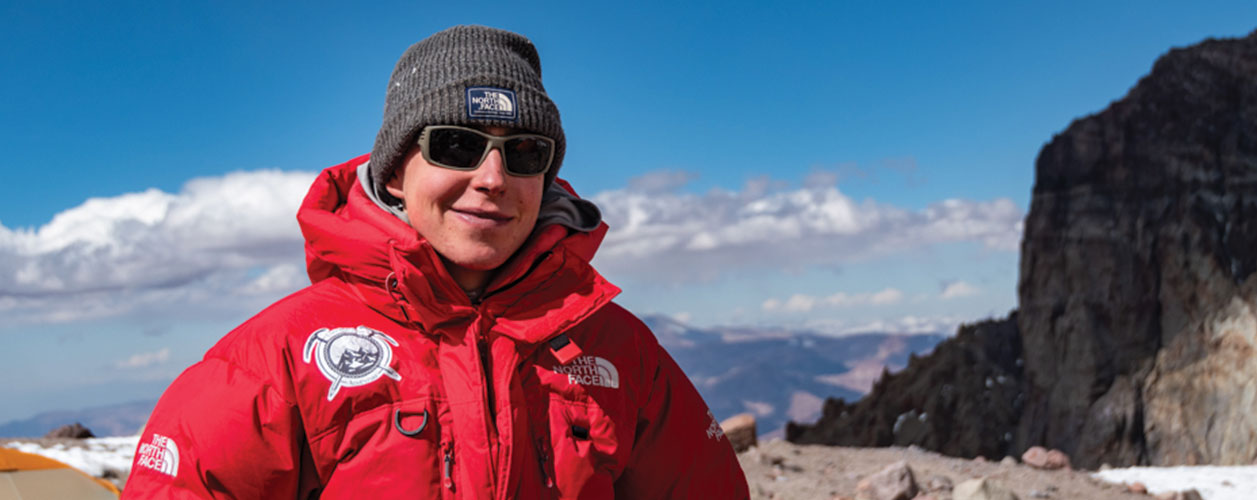

About the Gear Tester

Sam Chaneles

Sam Chaneles is an avid mountaineer and backpacker, climbing peaks in the Cascades, Mexico, Ecuador, and Africa, as well as hiking the John Muir Trail and off-trail routes in Colorado. He has climbed peaks such as Aconcagua, Mt. Rainier, Cotopaxi, Chimborazo, Kilimanjaro, and many more. Sam graduated with a B.S. in Mechanical Engineering from Georgia Tech. During his time there he was a Trip and Expedition Leader for the school’s Outdoor Recreation program (ORGT). He has led expeditions to New Zealand, Alaska, Corsica, France, and throughout the United States. Sam is based in Issaquah, WA just outside of the Cascade Mountains. You can follow Sam and his adventures on Instagram at @samchaneles, or on his website at www.engineeredforadventure.com.