From Hiking to Mountaineering: Making the Jump

How to Make the Transition into More Complex Terrain

Denali … Mt. Everest … Mt. Rainier. High peaks, snow-capped, ripping wind. These mountains evoke feelings of ruggedness and adventure. How do people develop the skills to get there? Not everyone grows up in the high mountains from a young age, there must be some way to develop the skills necessary to reach these remote places?

I resonate with these feelings; I grew up in Miami, Florida, hardly the place for high mountain adventures. While I would see images in National Geographic Magazine and on television as a kid, I wasn’t the young rock climber in the gym who climbed 5.12 at age 8, nor was I the baby who was stuffed in their parents backpack on mountain adventures.

‘Mountaineering’ is a blanket term used to describe “the sport or activity of climbing mountains” (per Oxford Dictionary). I’ll define it, for the purpose of this article, as:

Travel that includes a mix of hiking, snow travel, and scrambling or climbing over rock.

Mountaineering is an extension of hiking, backpacking, and basic backcountry skills. It takes fundamental skills, such as reading a map or following a developed path, and pushes them into more varied terrain. The key difference here is variety. Mountaineering involves a mixed skill set of hiking skills, snow-travel skills, and rock climbing/scrambling skills. I’ll focus on three categories and expound on the differences between hiking and mountaineering:

- Travel Surface

- Gear

- Route Planning

Travel Surface

Snow, Dirt, Rock. Mountaineering often involves a mix of all three.

Snow Travel can be a spectrum from walking over patches of snow to ice climbing. Travel over snow is often slower than beaten-in trail and can vary in difficulty throughout the day. In the morning, when the snow is firm, travel can be quick (with appropriate equipment); later in the day when the snow has softened, travel can be treacherous with postholing (falling through the snow surface).

Rock Scrambling involves moving over rocks and ridgelines where more than one ‘point of contact’ may be required. A ‘point of contact’ is a body part in touch with the surface; for example,

- a single point of contact would be considered one foot on the ground at a time (typical walking),

- Two points of contact would be a foot and a hand simultaneously (bracing yourself against a rock),

- Three points of contact would be two feet and a hand, or two hands and one foot,

- Four points of contact would be both hands and feet.

Rock scrambling is often done without ropes or forms of protection from a fall. Typically, scrambling is limited to ‘3rd’ or ‘4th class’ terrain (per Yosemite Decimal System), where ropes may or may not be used.

Rock Climbing involves moving through ‘5th class’ terrain of near-vertical or vertical rock where ropes and protection are often used. Think climbing up cliffs, steep ridgelines, or vertical rock faces.

Mountaineering blends different forms of travel, whereas hiking is centered around travel over dirt and bare earth. How do you progress into mountaineering from hiking? The best way is to ‘dabble’ in each of the forms of travel in bite-size chunks, first, to develop proficiency.

- Go on a rock climb with a friend. Top-rope first to get a sense of rope skills and how to move through near-vertical or vertical terrain. Even try a climbing gym first if outdoor rock climbing is too big a step up.

- Try hiking a trail in the winter when it’s snow-covered. Pick a familiar trail first, then maybe progress to an unknown trail. Practice moving through snow, learning the differences between bare earth and snow-covered trail.

- Take an Intro to Mountaineering course with a guiding company or local mountain organization (like Colorado Mountain Club, The Mountaineers, The Mazamas). These courses often cover the fundamentals and get you into the mountains with an experienced teacher.

- Read up on the skills and practice at home! The Freedom of the Hills, YouTube, and many other books can be a good way to introduce yourself to rope skills, planning principles, and other written knowledge in mountaineering.

Gear

Gear for mountaineering varies with the terrain surface involved. I’ll parallel the gear considerations to the terrain surface:

Snow Travel often requires the use of traction devices, such as crampons or micropsikes. Crampons are spikes that are attached externally to your shoe or boot to give you purchase over firm snow or ice. Their spikes are larger than microspikes, which are more of a chain mesh with a few small spikes intermixed. Crampons can vary in construction depending on their intended use case:

- Ice climbing crampons, which typically have a horizontal ‘front point’ for kicking your toes into vertical ice

- General 12-point crampons, used for most mountaineering

- General 10-point crampons, used for low-grade mountaineering and snow travel

Knowing how to fit and walk with crampons is a key skill for snow travel and mountaineering. You should practice first before attempting a climb, as walking and descending with crampons can add complexity.

In addition to crampons, snow travel often requires the use of an ice axe. Ice axes are used for additional protection when traveling over snow. They can be used for stopping yourself in the event of a fall, assisting with climbing near-vertical or vertical snow/ice, and stabilizing yourself. There are different types of ice axes for different purposes:

- A ‘piolet’ or vertically shafted ice axe, often used for general mountaineering

- A curved ice axe is often used for more technical mountaineering

- An ‘ice tool’ is used for vertical ice climbing and is specialized for swinging into ice

Just like with crampons, selecting and using an ice axe is a skill that requires practice. Learn to self-arrest, identify the appropriate tool for the job, and practice!

Rock Climbing with rope systems requires the use of harnesses, belay devices, protection systems, and ropes.

Harnesses are worn over the waist to secure you to rope systems. Different ropes can be used for different climbs (single ropes, twin ropes, static ropes, dynamic ropes). Rope systems are used in conjunction with belay devices, or devices that add friction to allow for precise control of the rope systems. When climbing, protection systems such as cams, nuts, and quickdraws (carabiners attached to slings) are used to protect the climber in the event of a fall.

Gear for rock climbing varies with the type of climbing done. Sport climbing involves climbing on rock where bolts are present. Quickdraws, carabiners, and slings are used with rope systems and belay devices in this type of climbing. Traditional climbing involves climbing on rock where no bolts are present and protection is added into cracks in the rock. Cams and nuts are used in this form of climbing with rope systems and belay devices.

Route Planning

Mountaineering often involves off-trail travel and self-navigation through complex terrain. There can be a mix of use-trail, beaten-in footpaths, and untouched surfaces to manage. Understanding the fundamentals of route selection and off-trail navigation are critical for mountaineering.

Guidebooks are a great resource for mountaineering routes, much more so than hiking. They often describe the difficult sections of the route, gear considerations that should be made, and can give an estimate of time/effort required.

Trip Reports are another useful resource for mountaineering, more so than hiking. Trip reports may be documented on forums like Mountaineers.Org, 14ers.com, CascadeClimbers.com, Facebook, etc. These are first-hand accounts from other climbers that describe the experience in great detail. It’s important to take these reports with a grain of salt, as they are subjective experiences from others.

Digital and Physical Maps are a fundamental tool that every mountaineer should have. A GPX track on a mapping app like Caltopo, Gaia, or OnX Backcountry is an excellent resource. It’s easy to use your phone throughout the day to make sure you are on track. However, any digital device that requires battery power should be supplemented with some form of physical map or route detail. If your battery dies or your phone breaks, you’ll be glad to have a backup.

Finally, understanding pacing is key. As mentioned before, travel across different surfaces is a key component of mountaineering. Your pace across snow will be different than across exposed rock ridges. To start, give yourself a conservative estimate like 1 mph or 500’-1,000’/hour to estimate how long a route will take you.

Practice, practice, practice. The key with developing any skill is repetition and gradual improvements over time. If you’re looking to elevate from hiking, backpacking, or trail running to more technical mountaineering, you’ll need to learn and practice skills related to off-trail navigation, rock climbing and scrambling, and traveling over snow and ice. Reach out to the community around you! Join a local outdoors club, find a guided course, or look for smaller adventures in your area to practice the skills you’ll need to reach your next summit!

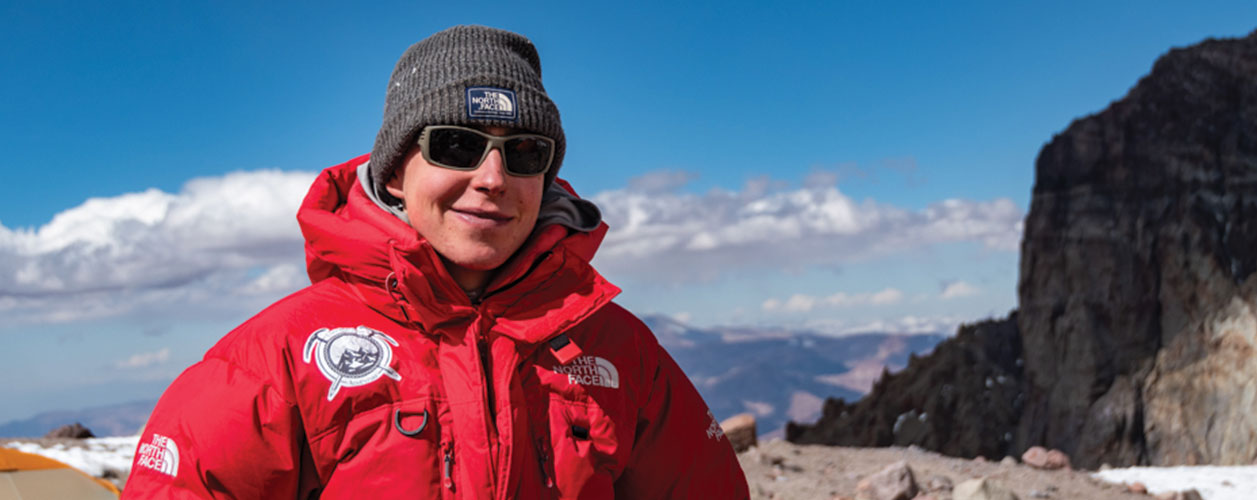

About the Gear Tester

Sam Chaneles

Sam Chaneles is an avid mountaineer and backpacker, climbing peaks in the Cascades, Mexico, Ecuador, and Africa, as well as hiking the John Muir Trail and off-trail routes in Colorado. He has climbed peaks such as Aconcagua, Mt. Rainier, Cotopaxi, Chimborazo, Kilimanjaro, and many more. Sam graduated with a B.S. in Mechanical Engineering from Georgia Tech. During his time there he was a Trip and Expedition Leader for the school’s Outdoor Recreation program (ORGT). He has led expeditions to New Zealand, Alaska, Corsica, France, and throughout the United States. Sam is based in Issaquah, WA just outside of the Cascade Mountains. You can follow Sam and his adventures on Instagram at @samchaneles, or on his website at www.engineeredforadventure.com.